How emotions are made

Neuroscience research in the past decades has shown that our brain gives meaning to our experiences and sensations, through concepts such as emotions.

Posted by

Published on

Thu 11 May. 2023

Topics

| Brain Research | Emotions | FaceReader | Facial Expression Analysis | The Observer XT | Emotion Recognition | Measure Emotions |

How to measure emotions of respondents

I regularly get this question from clients: “How do we measure the emotions of our respondents?” At this point, I explain that in order to get a good picture of the respondents’ emotional responses, you can use The Observer XT to monitor their overt behavior, FaceReader to measure their facial expressions, and psychophysiological measures to get an idea of what occurs on the inside. To combine and streamline these multiple types of measurements on one platform, NoldusHub® is the way to go.

After data has been acquired using one of these tools, another question often pops up: “Why does FaceReader measure so much anger?" Our product / website was not designed to elicit anger?!”

FREE WHITE PAPER: FaceReader methodology

Download the free FaceReader methodology note to learn more about facial expression analysis theory.

- How FaceReader works

- More about the calibration

- Insight in quality of analysis & output

How emotions are made

Total confusion

The first time I got this question, I was also confused. Surely the respondents were not truly angry, so why would they show an angry facial expression? It wasn’t until I read Lisa Feldman Barrett’s book “How Emotions Are Made (The Secret Life of the Brain)” that I fully understood how the classical view on emotions causes this confusion.

In this well-written book, Dr. Barrett convincingly argues that the classical view on emotions and how our brain works is based on a number of flawed premises that have been disproven by neuroscience research in the last two decades. Two flawed assumptions about emotions and our brain are:

- Each emotion is located in a specific part of the brain. For example, the amygdala (part of the limbic system, which plays a role in processing emotional reactions) is supposed to be the ‘fear center.’

- When the right stimuli are presented, a specific emotion is triggered, accompanied by a fixed facial expression.

First of all: read the book! Dr. Barrett does such a great job in explaining how our brain works and how emotions are made.

Emotions are created by our brain

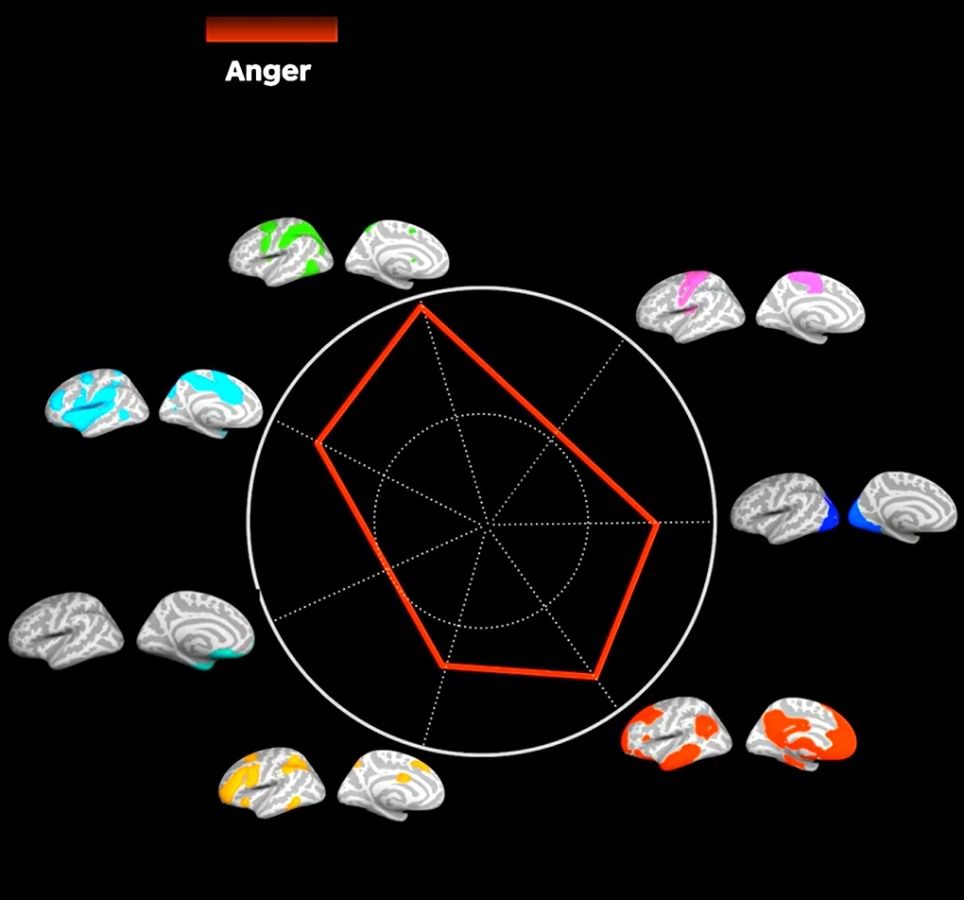

Neuroscience research in past decades has shown that emotions do not have ‘fingerprints’ in the brain. Different networks in the brain can create the same emotion. And yes, emotions are created by our brain. It is the way our brain gives meaning to bodily sensations based on past experience. Different core networks all contribute at different levels to feelings such as happiness, surprise, sadness, and anger.

Figure 1. Picture of seven core networks that form ingredients for the ‘recipe’ for feeling anger. A line closer to the perimeter of the circle indicates that this network shows a higher activity for the feeling of anger (this picture is a screenshot from a video created by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, hmhco.com).

What is going on: sensing and past experience

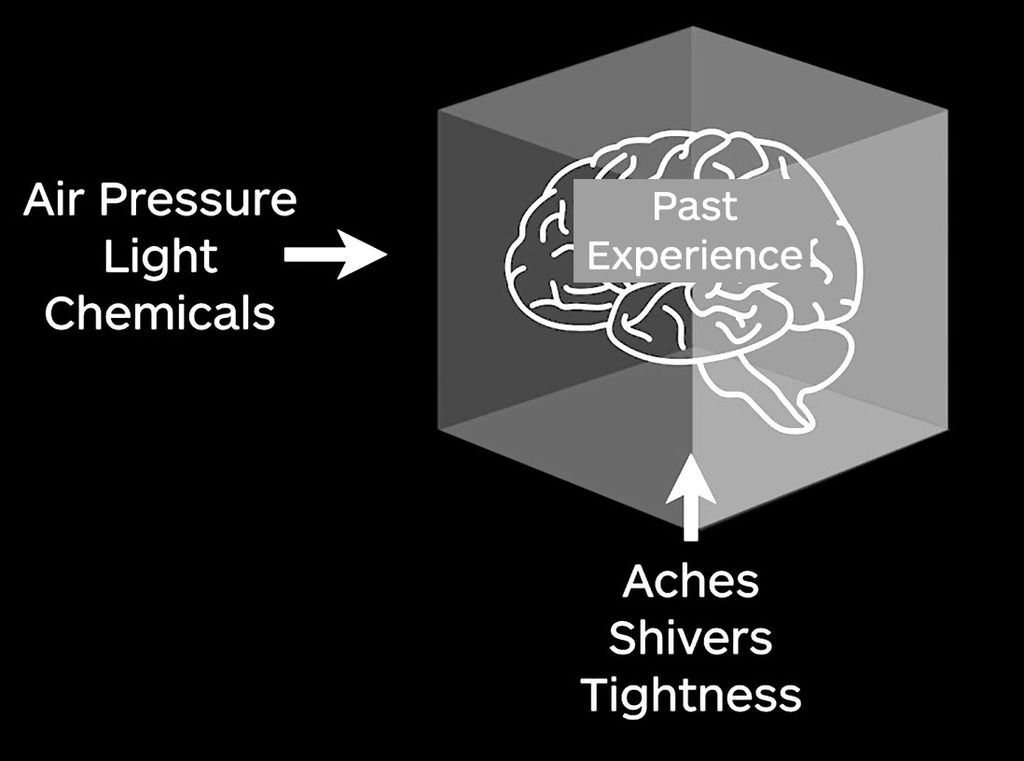

Let me try to explain a bit more. The interoceptive network in the brain continuously monitors your bodily sensations: your heart beating, your lungs filling/emptying, your intestines working, and your stomach (slightly) aching. Your brain (locked in its dark, silent box we call the skull) tries to figure out what these bodily sensations mean based on both the information it receives from the outside world through your senses and based on past experience.

Figure 2. Picture representing how our brain (stuck inside the dark box called skull) uses current and past information to make sense of what is going on. Information from the outside world comes in through the senses (air pressure, light, chemicals). Information from the inside world (aches, shivers, tightness) comes in via the interoceptive network. Past experiences are stored in the brain (this picture is an adapted screenshot from a video created by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, hmhco.com).

The main task of the brain is to keep you alive and well. To achieve this, it constantly monitors your inner and outer world and redistributes energy to the body part that currently needs it the most. While monitoring the outside world, the brain is not just a passive spectator.

How are emotions created in the brain

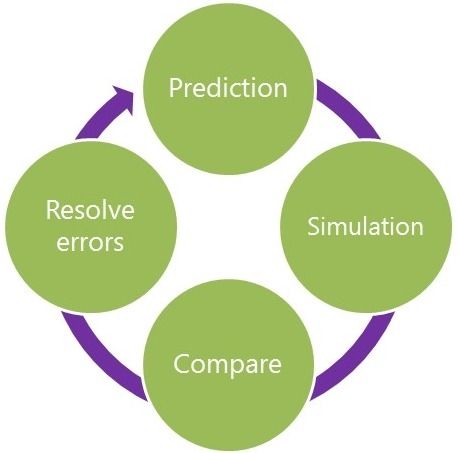

Neuroscience research has shown that the brain actually predicts and simulates the outside world. For this, our brain uses concepts. For example, when I mention the word/concept ‘apple,’ your brain immediately pictures an apple. It might be red, or green, and your brain might even simulate the touch of the smooth surface against your hand. If you’re hungry while reading this, try simulating the crunchy sensation and sweet/tangy taste when taking a bite out of your simulated apple.

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the brain’s basic process of monitoring the world. Based on ‘concepts’ that are built by past experiences it predicts and simulates the outside world. Your brain then compares the simulation with the real-world situation coming in via sensory input. If there is a mismatch, either the concept is changed, or the sensory input (see the snake-example below) (this picture is a screenshot from a video created by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, hmhco.com).

Let’s apply this to emotions. For example, you take a walk through a forest, and you suddenly hear/see the rustling of leaves. Based on past experiences, your brain predicts what’s going on. In this case, there might be a snake nearby in the bushes. Your brain starts to simulate the sights and sounds of a snake and prepares your body for action, i.e. running away as fast as you can.

To this aim, your heart rate goes up, you start breathing more deeply, and you start to feel agitated. The meaning your brain gives to this feeling might be ‘fear’ (which can be considered as just another brain concept, just like, ‘apple,’ ‘mother,’ ‘dog,’ or ‘chair’).

Three possible behaviors as outcome

There are three possible outcomes of this situation. A snake slithers out from underneath the bushes, and you make a run for it. Fear was your brain’s best guess for what just caused your bodily sensations.

The second possible outcome is that there is no snake, and it was just the wind. In this case, your brain corrects it prediction (a snake in the bushes), your body calms down again, and you make sense of your agitated feeling in some other way.

The third less likely but still possible outcome is that there actually is no snake but you still see one. In this case, your brain does not correct the prediction (see outcome two), but your brain’s simulation overrules the sensory input.

RESOURCES: Read more about FaceReader

Find out how FaceReader is used in a wide range of studies and how it can elevate your research!

- Free white papers

- Customer success stories

- Featured blog posts

What does our brain tell us?

To sum it all up, according to Lisa Barrett our brain continuously produces predictions and simulations, and so we experience a world of our own creation held in check by our sensory world. Our brain gives meaning to our experiences/sensations through concepts such as emotions.

Can we possibly measure emotions / the emotional state of a person? Stay tuned for a series of blogs that will address the question: How to measure emotions.

References

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Boston, MA, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Related Posts

Emotional responses to infant crying

Facial expression analysis in video content marketing