Social buffering in zebrafish

Shared sorrow is half a sorrow, according to the old proverb. New research indicates that social support is not only important for us humans, but also for zebrafish!

Posted by

Published on

Tue 25 Apr. 2017

Topics

| EthoVision XT | Video Tracking | Zebrafish |

Shared sorrow is half a sorrow, according to the old proverb. New research indicates that social support is not only important for us humans, but also for zebrafish!

Better recovery with social support

We cope better in a threatening or unpleasant situation if we are not alone, a phenomenon scientists call social buffering. We humans are not the only species that exhibit social buffering; several animals demonstrate this adaptation, which of course has some evolutionary advantages. The presence of conspecifics makes a threatening situation less dangerous, and thus the behavioral response to this situation is downregulated. Sounds pretty logical, right?

Zebrafish feel supported

Zebrafish are no exception. Faustino et al. recently found that zebrafish showed less fear in a threatening situation when they were not alone.

In their behavioral paradigm, the researchers exposed fish to an alarm substance. Some fish were alone, while others were exposed to conspecific cues – meaning that they were swimming in shoal water (olfactory cue only), were in visual contact with their shoal in an adjacent tank (visual cue only), or both (olfactory + visual cues).

Caught on camera

With the use of two cameras, fish were video monitored from the top and from a side view. EthoVision XT was used to track the animals and extract xyz coordinates. From these tracks detailed analysis of freezing behavior and erratic movements was performed to assess fear behavior in the zebrafish.

To validate correct behavioral analysis, results were compared to human observation using The Observer XT.

Seeing is believing

The results indicate that there was social buffering: zebrafish that were exposed to the aversive stimulus dealt with it better when they were not alone, as evidenced by less freezing behavior. The visual cue – being able to see their shoal – showed to be more effective than the olfactory cue (shoal water); size of shoal did not influence behavior.

Gaining more insight

Researchers also found that social buffering elicited a specific co-activation pattern in the brain, instead of specific activation of certain brain areas, similar to a pattern that is found in mammals.

This study adds to the growing understanding of the evolution of social buffering in social animals and the underlying mechanisms. The authors also hint at further research with zebrafish larvae and optogenetic techniques to get more in-depth insight at the circuit level.

References

Faustino, A.I.; Tacão-Monteiro, A.; Oliveira, R.F. (2017). Mechanisms of social buffering of fear in zebrafish. Scientific Reports, doi:10.1038/srep44329.

Related Posts

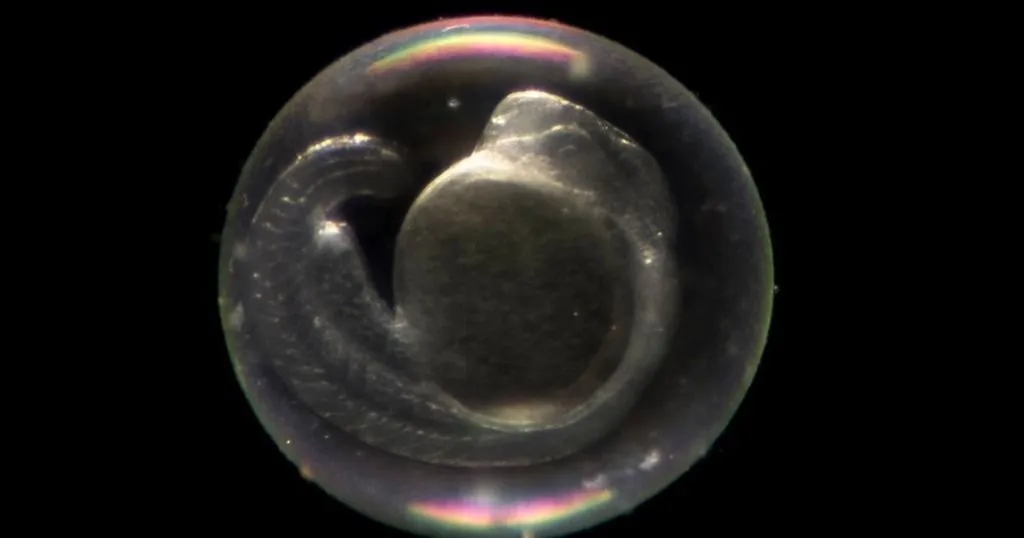

Zebrafish tracking to uncover subtle effects of embryonic alcohol exposure

Zebrafish as lab animal increasingly popular