Mice in the spotlight: why you should perform your tests in a home cage

Mouse models are essential for neuroscience research. Many tests are susceptible to bias. Home cage testing provides a number of solutions.

Posted by

Published on

Thu 06 Aug. 2015

Topics

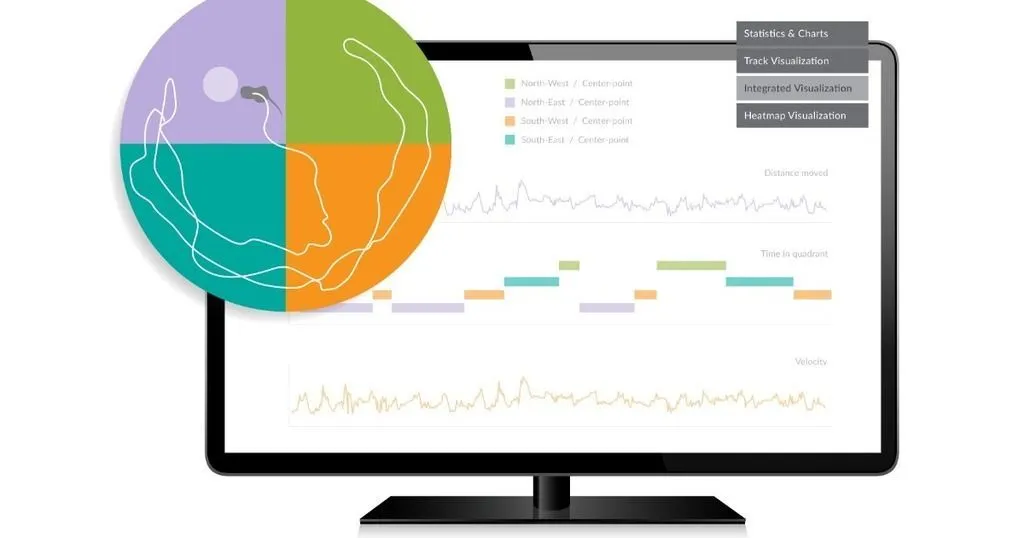

| Anxiety | EthoVision XT | Home Cage | Learning And Memory | PhenoTyper | Video Tracking |

Mouse models have proven to be essential in discovering the neurological underpinnings of diseases and to the development of a deeper understanding of genotype-phenotype relations. Behavioral phenotyping of these mice is very important, evidenced by the variety of tests that have been described in literature. Unfortunately, many of these tests are susceptible to bias, for example, testing in a novel environment. Bias can also result from handling animals prior to the tests, which can induce artificial behaviors that confound results.

Win-win-win

A number of researchers have found the answer to this problem in home cage testing. By letting the animal stay in its familiar environment researchers can prevent pretest stress and the novelty of the environment from influencing the behavior of the animal. Better welfare, better results, and improved efficiency. It seems like a win-win-win situation.

Emmeke Aarts and her colleagues thought so too, and they have developed and validated a mild anxiety test in the PhenoTyper home cage system. By performing this test in a home cage, they not only prevented bias introduced by handling or the novel environment, it also allowed them to use the baseline behavior of the mice previous to the test as a control measure.

In the spotlight

Their test is a light spot test, which uses the mouse’s natural aversion to bright light. They confirmed the anxiogenic effect of this test through the use of Diazepam, a common anxiolytic drug.

Mice are nocturnal animals. Aarts’ light spot test takes advantage of the mouse’s natural tendency to peak in activity during the beginning of the night, and of its photophobia. By aiming a light beam at the feeding station, the researchers presented the mice with a mild aversive stimulus. The decrease in time spent outside of the shelter (compared to previous baseline measures) was taken as a measure of anxiety. As multiple tests can be executed in the home cage, they also performed learning tasks to see if these would influence the light spot test results.

Staying in

In a home cage environment, test protocols can take several days. The first experiment Aarts and her colleagues performed lasted for four days: the first three day were reserved for habituation, and the light spot test took place on the fourth night. During habituation, baseline behavior was measured, allowing for the mice to serve as their own control group. The researchers also included a group of mice that would not undergo the light spot test, serving as an external control group. The light spot indeed made the mice stay in their shelter more. After the light was turned off, the mice seemed to compensate for lost time, spending more time outside. Maybe they were hungry?

Getting bold

During the second experiment, Diazepam was used to verify if the light spot had an anxiogenic effect. Since Diazepam is a known anxiolytic, the mice were expected to be less anxious in regards to the light presentation after receiving Diazepam. This proved to be the case: mice that had consumed the anxiolytic spent more time in the light than mice that had not consumed the drug. Despite a decrease in anxiety-like behavior among the mice receiving the anxiolytic, the drugs did not completely remove the anxiogenic effect of the spotlight on the mice. Under the influence of Diazepam, the mice still spent less time outside of the shelter than they did on light-free nights. When the test was repeated after a light-free night, the Diazepam seemed to have less of an effect. Though it made a noticeable impact on behavior, the data did not reach statistical significance.

Mice taking drugs

It is important to note that drug administration can be invasive and thus influence behavior. To avoid this, the researchers used a voluntary intake method by creating a fatty palatable matrix with the Diazepam in it. The mice voluntarily took their drugs.

Testing for a week

The third experiment lasted for six days, again beginning with three days of habituation and baseline measurements. On the fourth night, the mice were subjected to a learning task: they had to hop onto the shelter to receive a food reward. On the fifth night, an avoidance test was performed, in which the mice were required to cope with the fact that using their favorite of two entrances into the shelter would cause a light to be turned on in the shelter. To avoid the illumination, the mice had to cope: either enter through the other side or stay outside. This test was repeated on the sixth night in combination with the light spot test. A control group was subjected to the same protocol, but without the spotlight on the sixth night.

Not surprisingly, test order effects became apparent. The learning tasks seemed to have shifted the circadian rhythm of the mice, resulting in a different effect of the light spot test as compared to the previous experiments. There was no longer a direct behavioral effect of the light spot test, and after the test, the mice spent less time outside the shelter, instead of more.

Into the future

This study shows that the home cage light spot test is as effective as classical anxiety tests, without confounding factors such as handling and environmental novelty. Also, in this test, the aversive stimulus is mild and ecologically valid. As in other situations, test order matters. Future studies by these researchers will focus on identifying behavioral differences between mutants and wild-type mice in similar settings.

Read on

Aarts, E.; Maroteaux, G.; Loos, M.; Koopmans, B.; Kovačević, J.; Smit, A.B.; Verhage, M.; Sluis, S. van der; Neuro-BSIK Mouse Phenomics Consortium. (2015). The light spot test: measuring anxiety in mice in an automated home-cage environment. Behavioural Brain Research, 294, 123-130 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.06.011.

Related Posts

NIH Grant Writing Series: Insider Tips for Funding Success - Part 2

Everything you need to know about EthoVision XT